COVID-19 is not the first pandemic caused by a novel strain of a virus affecting the upper respiratory tract. Over the past 100 years, pandemics have been caused by novel forms of influenza and other coronaviruses, such as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS) and Middle East Severe respiratory syndrome (MERS). Common complications of each of these infections include pneumonia which can lead to secondary bacterial infections requiring treatment with antibiotics.

As more patients are hospitalized due to severe COVID-19 infections, often due to worsening respiratory symptoms requiring ventilation, an increasing number of patients have been acquiring secondary bacterial infections that require treatment with antibiotics. This trend has given rise to the concern that the pandemic may exacerbate an existing crisis – antimicrobial resistance (AMR) – which has been growing in urgency in recent years, even prior to the pandemic. That is because antibiotic resistance is caused by the very use of antibiotics themselves, as the bacteria evolve to develop resistance against the antibiotics.

Recent evidence confirms the growing fear about the link between COVID-19 and increasing AMR is well-founded. Not only have these infections become more common as a result of the pandemic but they have also become more deadly.

A recent meta-analysis examining the prevalence of secondary infections in COVID-19 patients found high rates of co-infection with antibiotic-resistant pathogens. Greater than 25% of COVID-19 patients were co-infected with staph infections and more than half of those staph infections were antibiotic-resistant infections known as MRSA.

A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) study examining hospital-acquired infections in COVID-19 patients found increased cases of these infections relative to pre-pandemic levels. These increases differed by state and grew over time. In particular, central-line-associated bloodstream infections – a common hospital acquired infection caused by antibiotic resistant pathogens – saw high rates of increase. For example, Arizona’s incidence rates for these infections were nearly 150% higher in the second quarter of 2020 relative to the same time frame prior to the pandemic. Incidence rates in Massachusetts doubled over that same period.

Another recent study examined the outcomes of secondary infections in hospitalized COVID-19 patients and compared them to outcomes for patients hospitalized due to the flu. The study found not only a higher risk of infection in COVID patients but that these infections were also associated with a higher risk of death.

The world urgently needs new antimicrobials to help fight the rise of drug-resistant infections. This was true prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, and it remains increasingly true today as we witness the threat of antimicrobial resistance gain strength before our eyes. We simply cannot be prepared for the next global health crisis if we do not address the growing threat of antimicrobial resistance.

Prior to the pandemic, this threat was estimated to affect the lives of 3 million Americans and result in 48,000 deaths annually. Similarly, a 2017 World Bank Group report on drug-resistant infections estimated that prior to the current crisis, unless action is taken, antimicrobial resistance could take 10 million lives annually by 2050, a higher death toll than cancer. Moreover, if we fail to address this crisis, many modern medical improvements that depend on antibiotics – such as routine surgery, cancer therapy and treatment of chronic disease – may be jeopardized.

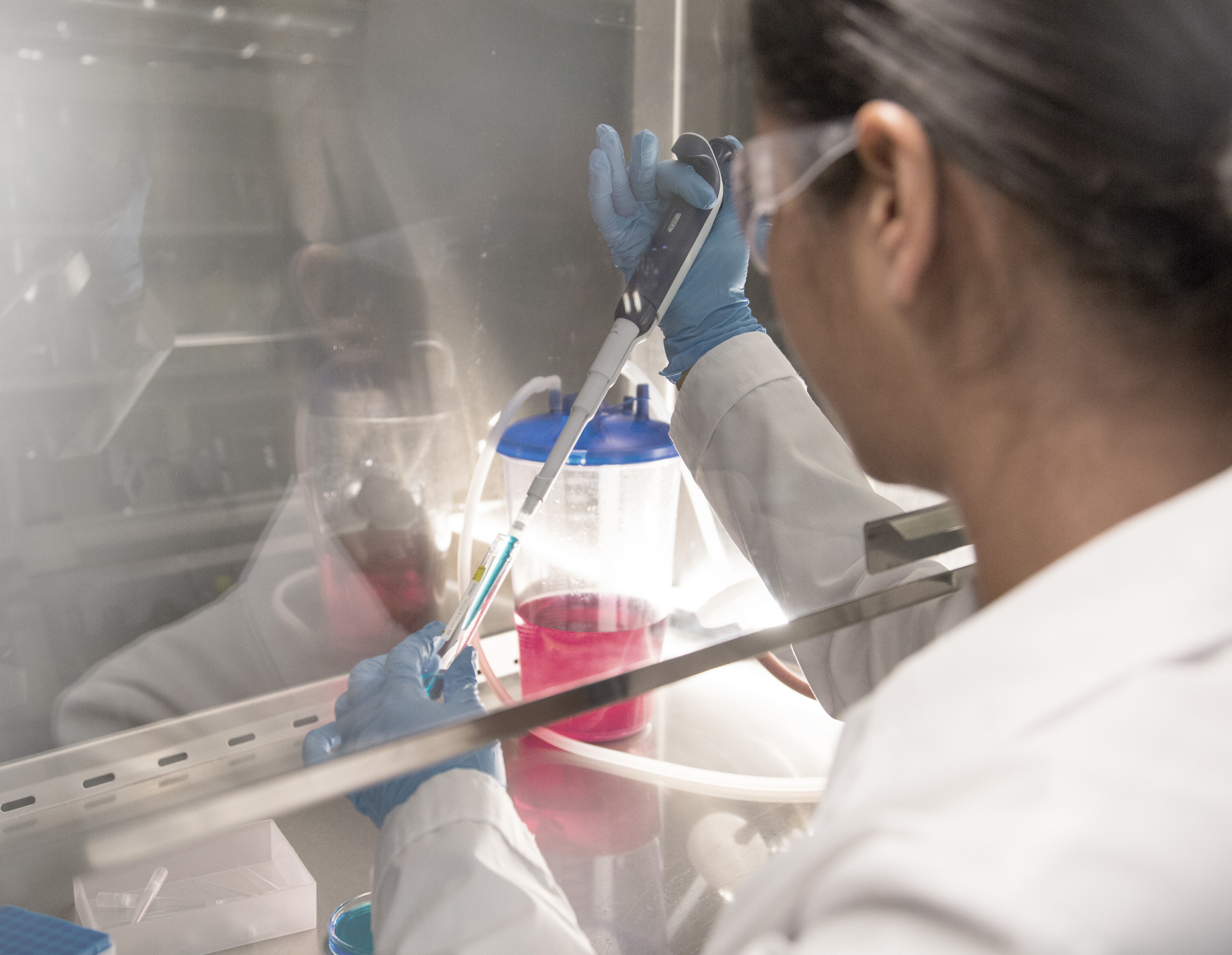

Unfortunately, our current arsenal of antimicrobials is not equipped to handle increasing levels of resistance, and the pipeline of new antimicrobials needed to stem the tide of resistance has been on the decline. Yet developing a single antimicrobial medicine can take anywhere from 10-20.5 years and among new classes of antibiotics in the preclinical stage, just 1 in 30 are ultimately successful and reach patients.

A fundamental challenge with developing new medicines to combat antimicrobial resistance is that a novel antimicrobial ideally should be used in a limited set of circumstances. And due to the limited size of the market it can be challenging for biopharmaceutical research companies to be commercially successful. Owing to these challenges many biopharmaceutical research companies have declared bankruptcies in recent years or exited the field.

To overcome the market’s failure to drive innovation for antimicrobials a unique innovation ecosystem has evolved to address these challenges, including innovative partnerships and initiatives within and between the public and private sectors including the AMR Action Fund. Unfortunately, the unique innovation ecosystem that has evolved to address AMR cannot solve these problems alone.

In order to stem the tide of antimicrobial resistance, which threatens modern medicine as we know it and leaves us extremely vulnerable to not only the current pandemic but the next one, additional policy reforms are urgently needed to create a more sustainable environment for antimicrobial research, development and commercialization to ensure a robust pipeline of future treatments.

A recent study by Kevin Outterson, executive director of CARB-X at Boston University, a global non-profit partnership dedicated to advancing antimicrobial research, presents a call to action for government intervention in the U.S. and abroad to implement policy initiatives that delink payments for antibiotics from volume once an antibiotic is approved – otherwise known as “pull incentives.” The study estimates the appropriate size of global pull incentives for antibacterial medicines, such as the subscription model proposed in the PASTEUR Act, finding that these incentives must value an innovative antimicrobial that is brought to market at several billions of dollars in order to be effective. The amounts proposed in the PASTEUR Act, which was reintroduced this week as part of Cures 2.0, align with these estimates.

This Antimicrobial Awareness Week is the time for Congress to take a meaningful first step towards addressing the growing threat of AMR by holding a hearing on this critical issue. Along with our government’s commitment to addressing the current pandemic, we can be prepared for the next public health emergency if we all work together to ensure a sustainable pipeline for new antimicrobials for this crisis and those in years to come.